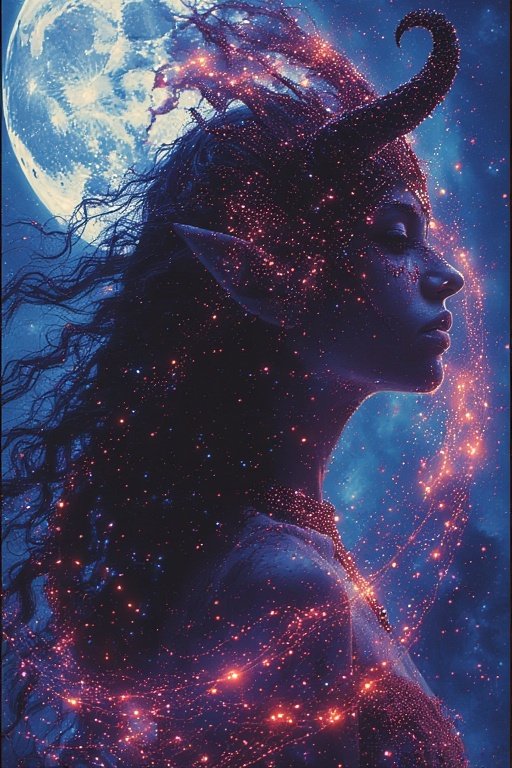

Four primordial female demons that often plague men’s dreams

Lilith is a demon that is said to be the first wife of Adam. She was created from the same clay as him, but she refused to submit to him. For this, she was banished from Eden. Lilith is often associated with sexuality and chaos. In some stories, she is also said to be the mother of all vampires.

The Nahemah demon is a creature of nightmares. It takes the form of a beautiful woman, but has the head of a serpent. This demon is said to be responsible for causing people to have bad dreams. It is also said that the Nahemah can enter into people’s dreams and control them. Nahemah was the daughter of Lilith, the primordial first woman and was a beautiful and powerful succubus who tempted men with her seductive ways.

Agrat Bat Mahlat is a demoness in Jewish mythology who tempts people into sin. She is often depicted as being beautiful and seductive. Agrat Bat Mahlat is said to be the cause of many people’s downfall.

The demon Eisheth is known to be a seductress. She often takes the form of a beautiful woman in order to lure men into her bed. Once she has them under her spell, she will drain them of their life force. Eisheth is also known to be able to shapeshift into other forms, such as that of a snake or a bird. She is a dangerous demon and should be avoided at all costs.

The Primordials do not belong to the realm of explicit horror or immediate violence. Their power lies not in attack, but in silent proximity. They are beautiful—not according to human standards, but in a way that seems to predate all rules, a beauty that disarms precisely because it does not try to please. There is something slightly misplaced about them, a subtle imperfection that unsettles the eye and yet holds it captive.

The presence of these entities does not impose fear; it dissolves it. What takes its place is fascination. A difficult-to-name sense of recognition, as if something ancient were being awakened without asking permission. Their sensuality is not expressed through obvious gestures or excess, but through absolute calm, through the confidence of those who do not need to prove anything to be desired.

There is no direct threat, no extended claws or shouted warnings. The danger lies precisely in the absence of conflict. They do not take—they offer. And what is offered is not merely pleasure, but the possibility of crossing an inner threshold, of briefly abandoning the structures that keep the world ordered and predictable.

Perhaps that is why they were turned into monsters over the centuries. It is easier to fear what attacks than what invites. The Primordials remain at the margins not because they are grotesque, but because they are irresistible. And before them, the true question was never “how do we survive?”, but rather: how far are we willing to accept the invitation?